Top 11 Viewzone Stories

2012: Doomsday Facts

Dan Eden investigates the hard science behind the real doomsday events.

The Last Doomsday

A scientific look at the last human extinction event 14500 years ago. Will it happen again?

Left Brain:Right Brain

We have two brains that don't always argee and sometimes fight for control. Can facial features shed light on which brain controls our thoughts? Great article by Dan Eden with photographic analysis of many popular figures.

The Color Preference Personality Test

Select your favorite colors and see what this on-line test reveals. Requires JavaScript.

We're Not From Here!

Recent evidence suggests that we are not part of the Milky Way but a dwarf galaxy being assimilated.

Smallpox: The Weapon

A review of what we know about this deadly virus. Is it gone? Really?

How to read eyes!

What do professional interrogators look for to see if you are telling a lie? Can anyone do this?

Decorating with Feng Shui

Nancy Uon gently introduces you to the basics and shows how to best arrange your living space.

Handwriting Analysis

What can be learned about you through your handwriting. Some famous mysteries are described and lessons are given.

Money: what is it?

This Dan Eden article starts with the history of money and describes the current economics that have resulted in the rapidly declining US Dollar.

The Philadelphia Experiment

Did the US Navy succeed in making the US Liberty invisible?

The Stonehenge Observatory By Dean Talboys At the start of summer 2006 I probably knew as much about Stonehenge as the next man -- it's a collection of big old stones, or megaliths, set in a circle on the gently rolling chalk hills of Salisbury Plain in the English county of Wiltshire.

You may be wondering why anyone is still interested in the site. After all, so much has been written about it in the past 100 years there can be nothing left to discover, can there? If only it were that simple because, try as they might to pigeon-hole the site, Stonehenge poses a rather difficult problem for the archeologists.

Almost every attempt to recreate techniques believed to have been used to transport, prepare and erect the stones is done so from the point of reinforcing the Neolithic theory.

A re-evaluation by the Ancient Monuments Laboratory (AML) of radiocarbon datable material recovered during 20th century excavations of the site was clearly aimed at reinforcing these established phases.

It is against this backdrop that I attempted to publish a paper documenting my own theory some six months into my research. Looking back, to be honest, it was a hastily prepared conclusion I felt keen to rubber-stamp as my own and deserved no more attention than it achieved. Undeterred by the lack of official or media response I continued researching the subject of Stonehenge in books, video, and on the Internet.

Most authors provide little more information than can be obtained from R. J. C. Atkinson's book, Stonehenge, published in 1956, and default to the techniques for moving and erecting stones he describes. Even Gerald Hawkins, author of the much maligned Stonehenge Decoded in which he 'proved' the builders capable of astronomical calculation far ahead of their time, felt obliged to stick to Atkinson's sequence of construction and subsequent archeological dating of such.

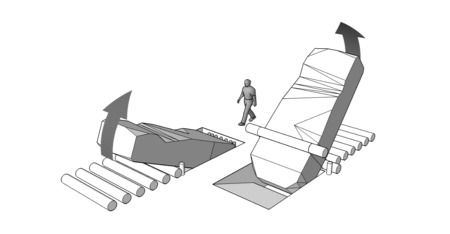

I too may have fallen into this trap had it not been for Google Sketchup. This incredibly powerful yet easy to use software allowed unparalleled access to the site via 3D models I had created using data from a variety of sources, and used in combination with CyberSky astronomical software, I was able to test theoretical alignments as well as add weight to my own theory. However, it was in using the models to provide illustrations for the book that I realized a consequence of the method Atkinson adopted to erect the Sarsen pillars -- the orientation of the flat inner face meant they could only have been raised from outside the circle. It was only one of a number of inconsistencies which were to cast doubt upon the established sequence of construction and dates, a doubt that was further corroborated following a thorough examination of the AML study.

By the end of 2007 I was reasonably certain my theory provided a credible alternative to any other, including the 'archillogical' interpretation of Stonehenge as a Neolithic place of ritual worship. Hawkins had been right about the outlying stones but they could only have been placed following severe erosion of the bank which would have otherwise rendered them useless. Other theories rely on a uniformity of stone and symmetry that is absent in all but the Sarsen lintel ring. Still more totally ignore features for which they have no use or explanation.

Stonehenge is too precise an arrangement to be simply a temple and yet too crude in the choice of material to be an astronomical observatory -- that is, until you fill it with water at which point the central setting of stones provides a firm base from which to observe a reflection of the Sun, Moon and stars. There could be no other reason for paying such close attention to the form and finish of a lintel ring that would remain out of sight to observers at ground level, and especially so when such little attention had been paid to the pillars supporting it.

Contrary to the many stylized models of Stonehenge the pillars are not of a uniform shape and size (and never were) neither are the gaps between them, yet much is made of their placement in aligning on or obscuring the view of various events. The pillars are purely structural and well suited to the purpose. Another reason to believe the lintels provided a firm base on which to move around is the technique used to secure them in place. It's not as if 7 tons of rock is likely to slip off two 30 ton pillars set 1m (3ft) into the ground, and yet the builders felt it necessary to use three different methods to join them all together. The surrounding hills still provide an ample supply of water today in the form of an unconfined aquifer and there is reason to believe it the level of the water table even higher in the past. Features within and around the site provide examples of how that water could be accessed and maintained within the confines of the henge.

For the first time every feature within the henge could be accounted for in a single, functional unit. However, in closing the door on one mystery I had opened the door to another of even greater magnitude. For my theory to be correct, the history of the Earth has to be wrong.

There is, of course, much more disclosed in my book, The Stonehenge Observatory. It includes a full cross-examination of the AML study, an explanation of the astronomical problems faced by the builders, alternative theories, and a full description of the features. But paper alone never really does justice to the site. Previous authors have reverted to long-winded descriptions of the stones with Ordnance Survey style plans for reference, or wire-frame diagrams of what the site would have looked like. In an attempt to provide the reader with as much access to the site as possible without the need to be there in person (which would require a time-machine to see how it was originally) I have made the 3D models available online at:

www.stonehengeobservatory.com.

The web site is designed to compliment the book, so don't expect too much in the way of commentary. The models are, however, very interactive with the option to hide or show features, pan and zoom manually or with the help of a site plan and an eBook version of The Stonehenge Observatory is available for those of you who can't wait for the printers. There is also an animated reconstruction of the destruction of the site from which it is possible to see the extent of the damage to individual stones. The destruction of Stonehenge is as much a mystery as how it was built.

There can be no doubt that Man figured largely in the removal of fallen stones but you need only look to the 20th century restoration of the site to realize how the sheer size and foundations of those left standing poses more of a problem for the scavenger than it ever did for the builder. Large cranes, gantries and cradles were essential to lift megaliths still buried after so many centuries. It is also clear that erosion of the site exposed some foundations sufficiently for the wind to take its toll, but not to such an extent that the entire southwestern sector would be demolished, and though the scale of the damage would suggest a tidal wave or earthquake, the pattern of destruction says otherwise. To this end, what I consider possible in The Stonehenge Observatory can only invite scorn from the academic community to which I do not belong, but the true age of Stonehenge and the event which lead to its destruction, and what can only be described as a red herring of truly astronomic proportions, are corroborated in studies by members of that very community.

New! Stonehenge Stones Cast Serious Doubt over [Stonehenge] Bluestones dated to 12,000BC

Dean Talboys is a consultant systems analyst based in Malaga, Spain.

|

Having grown-up in England I'd even had the opportunity to visit the area as a schoolboy, although I must say I was more interested in running up and down the slopes of neighboring Avebury than listening to the master droning on about how the site was constructed and by whom. Little had changed almost forty years later, England in the World Cup proving far more exciting than the antics of their Neolithic ancestors. So when my ten-year-old daughter asked why anyone would want to use such big stones to build Stonehenge in the first place my answer was appropriately glib, but it got me thinking. In fact it prompted a very bizarre experiment followed by two years of intense research culminating in a book, The Stonehenge Observatory.

Having grown-up in England I'd even had the opportunity to visit the area as a schoolboy, although I must say I was more interested in running up and down the slopes of neighboring Avebury than listening to the master droning on about how the site was constructed and by whom. Little had changed almost forty years later, England in the World Cup proving far more exciting than the antics of their Neolithic ancestors. So when my ten-year-old daughter asked why anyone would want to use such big stones to build Stonehenge in the first place my answer was appropriately glib, but it got me thinking. In fact it prompted a very bizarre experiment followed by two years of intense research culminating in a book, The Stonehenge Observatory. It has helped define a phased sequence of construction spanning 1,500 years where erection of the largest stone groups, the Trilithons, at the center of the monument would require the builders to negotiate the Sarsen Circle during their positioning and final erection (it's worth noting how the recreation of construction techniques is always performed in isolation and with neatly squared-off blocks of pre-cast concrete).

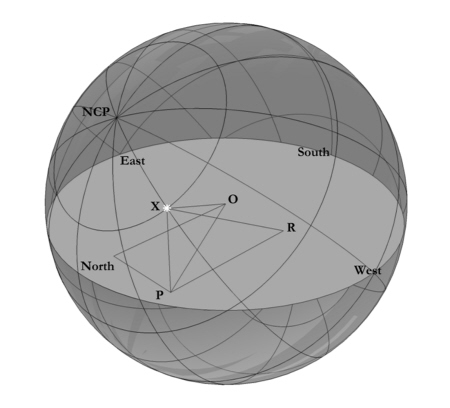

It has helped define a phased sequence of construction spanning 1,500 years where erection of the largest stone groups, the Trilithons, at the center of the monument would require the builders to negotiate the Sarsen Circle during their positioning and final erection (it's worth noting how the recreation of construction techniques is always performed in isolation and with neatly squared-off blocks of pre-cast concrete).  At the same time (the end of 2007) I was struggling with the geometry of projection. It was proving impossible to provide a geometrical method to compensate for the orientation of the site around 50° east of north without resorting to trig tables, and I wanted to show how the stars could be plotted mechanically. The orientation of the site towards the longest day of the year, the summer solstice, lends weight to the idea that it was intentionally aligned on the event, but the association is tenuous for several reasons, none least of which being the tendency for the event to move left and right according to the Earth's changing angle of tilt. Following a dialogue with a professor in astronomy I decided to look at the problem from a completely different angle, literally, at which point everything fell into place. Not only was the geometry problem solved, there was also an explanation for the positions of the Trilithons within the Sarsen circle in providing a permanent record of the Moon's northern and southernmost standstills.

At the same time (the end of 2007) I was struggling with the geometry of projection. It was proving impossible to provide a geometrical method to compensate for the orientation of the site around 50° east of north without resorting to trig tables, and I wanted to show how the stars could be plotted mechanically. The orientation of the site towards the longest day of the year, the summer solstice, lends weight to the idea that it was intentionally aligned on the event, but the association is tenuous for several reasons, none least of which being the tendency for the event to move left and right according to the Earth's changing angle of tilt. Following a dialogue with a professor in astronomy I decided to look at the problem from a completely different angle, literally, at which point everything fell into place. Not only was the geometry problem solved, there was also an explanation for the positions of the Trilithons within the Sarsen circle in providing a permanent record of the Moon's northern and southernmost standstills.