|

Homeless camps cover 50 acres in Hawai'i

By Dan Nakaso

Jun 27, 2010 WAIPAHU - HAWAII -- Pastor Joe Hunkin picked his way around rusted car axles, propane tanks and two-by-fours studded with bent nails to find a homeless encampment where people have been cooking and sleeping directly behind Waipahu High School, in an area that received unwanted national attention this month.

"The school is right over there," Hunkin said last week. "This isn't right." The strip of land is bounded by Waipahu High School on one side and the calming waters of Pearl Harbor's Middle Loch on the other, where the Navy's mothball fleet sits idle. It's the most visible portion of an enormous homeless encampment that stretches five miles over approximately 50 acres of city, Navy and state land that serpentines around Waipio Point Access Road, the Ted Makalena Golf Course and the city's Waipio Soccer Complex and back down to Pearl City in the opposite direction, said Beth Chapman, who uncharacteristically lost a suspect in the swampy brush last year after five straight days of searching the area with her husband, Duane "Dog" Chapman, and their bounty hunting family. In an episode of "Dog The Bounty Hunter" that aired on the A&E network two weeks ago, the Chapmans mounted mo-peds and switched their SUVs into four-wheel drive to navigate the area, where they discovered about 60 different encampments, Beth Chapman said last week in a telephone interview from Canada, where "Dog" was on a publicity tour.

By Paul Thompson A century and a half ago it was at the centre of the Californian gold rush, with hopeful prospectors pitching their tents along the banks of the American River. Today, tents are once again springing up in the city of Sacramento. But this time it is for people with no hope and no prospects. With America's economy in freefall and its housing market in crisis, California's state capital has become home to a tented city for the dispossessed.  Rich and poor: The tents and other makeshift homes have sprung up in the shadow of Sacramento's skyscrapers.

Shanty town: The tent city is already home to dozens of people, many left without jobs because of the credit crunch. Those who have lost their jobs and homes and have nowhere else to go are constructing makeshift shelters on the site, which covers several acres. As many as 50 people a week are turning up and the authorities estimate that the tent city is now home to more than 1,200 people. In a state more known for its fantastic wealth and the glitz and glamour of Hollywood, the images have shocked many Americans. Conditions are primitive, with no water supply or proper sanitation. Many residents have to walk up to three miles to buy bottled water from petrol stations or convenience stores.

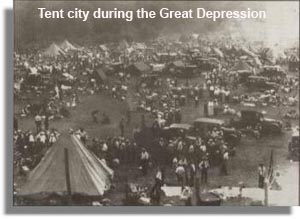

Tammy Day, a homeless woman, cooks potatoes on a campfire at the site At other times, charity workers arrive to hand out free food and other supplies. Joan Burke, who campaigns on behalf of the homeless, said the images of Americans living in tents would shock many. 'It should be an eye- opener for everybody,' she said. 'But we shouldn't just be shocked, we should take action to change things, because it's unacceptable. 'It is unacceptable that in this day and age we have gone back to a situation like we had during the Great Depression.'  Authorities in Sacramento, where Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger has his office, admit the sight of families living in such poverty is not pretty. But faced with their own budget crisis and a £30billion deficit, they have had little choice but to consider making the tent city a permanent fixture. The city's mayor Kevin Johnson said: 'I can't say tent cities are the answer to the homeless population in Sacramento, but I think it's one of the many things that should be considered and looked at.'

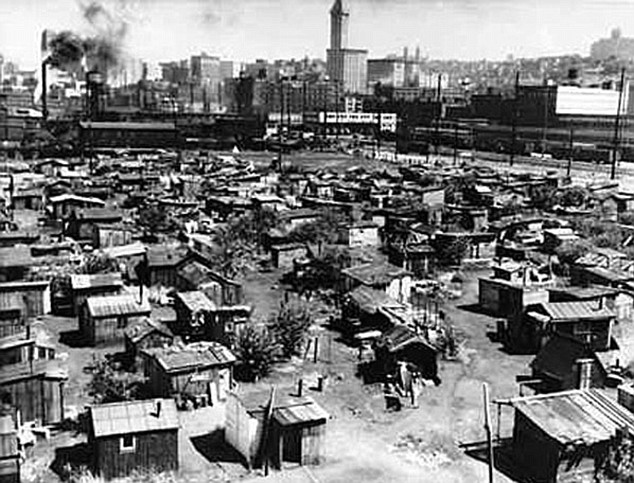

Shanty towns sprung up during the Great Depression as people lost their jobs and homes.

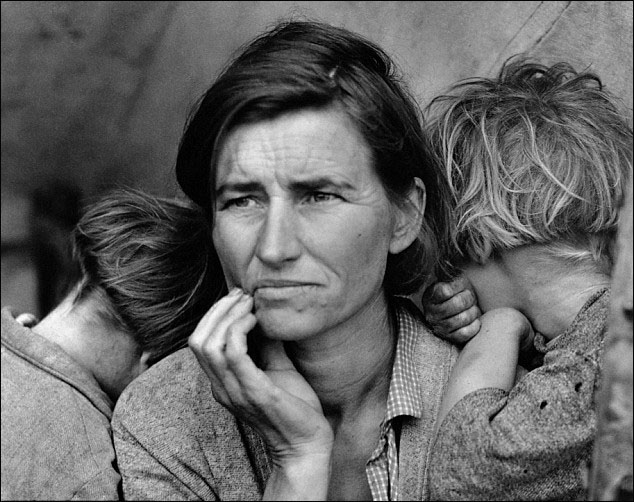

Migrant Mother: Dorothea Lange's famous photograph from the Great Depression features Florence Owens Thompson, 32, a mother-of-three who had just sold the family's tent to buy food. As America's most powerful state California had the same gross domestic output as Italy and Spain, but it has been among the hardest hit by the recession and housing crisis. Foreclosure rates last year rocketed by 327 per cent, with up to 500 people a day losing their home. Coupled with massive job cuts that have seen one in ten workers laid off, many people who once enjoyed a middle class existence are now forced into third world conditions. Former car salesman Corvin and his wife Tena are among the newest residents of the tent city.

Tent city residents queue up to receive supplies handed out by a local charity. The couple, who are in their fifties, lost their home and jobs around the same time. With homeless shelters full in Sacramento, they had little choice but to use what savings they had left to buy a tent. The couple admit they have yet to tell their grown-up children about their hand-to-mouth existence. Tena said: 'I have a 35-year-old son, and he doesn't know. I call him, about once a month and on holidays, to let him know that I'm well and healthy. 'He would love me anyway, but I don't want to worry him.' The shame of Sacramento's tent city was given a much wider airing after it was featured on the Oprah Winfrey show which is watched by more than 40million people a week. Many of those who have found themselves homeless worked in the building trade. But with no new home builds and as many as 80,000 people losing their job every month, there is little chance of employment. Governor Schwarzenegger last month approved a budget to address the state's deficit, ending a three-month stalemate among lawmakers. As well as increasing taxes, he has imposed drastic cuts in education, healthcare and services that will affect everyone living in the state. Many of those living in the tent city are pinning their hopes on President Obama's $787billion stimulus package which is aimed at rescuing the economy and creating jobs. The President has also announced plans to save the homes of nine million people from foreclosure by restructuring their mortgage debt.

By EVELYN NIEVES RENO, Nev. (AP) -- A few tents cropped up hard by the railroad tracks, pitched by men left with nowhere to go once the emergency winter shelter closed for the summer. Then others appeared -- people who had lost their jobs to the ailing economy, couldn't repay their loans, or newcomers who had moved to Reno for work and discovered no one was hiring. Within weeks, more than 150 people were living in tents big and small, barely a foot apart in a patch of dirt slated to be a parking lot for a campus of shelters Reno is building for its homeless population. Like many other cities, Reno has found itself with a "tent city" -- an encampment of people who had nowhere else to go. From Seattle to Athens, Ga., homeless advocacy groups and city agencies are reporting the most visible rise in homeless encampments in a generation. Nearly 61 percent of local and state homeless coalitions say they've experienced a rise in homelessness since the foreclosure crisis began in 2007, according to a report by the National Coalition for the Homeless. The group says the problem has worsened since the report's release in April, with foreclosures mounting, gas and food prices rising and the job market tightening.

The phenomenon of encampments has caught advocacy groups somewhat by surprise, largely because of how quickly they have sprung up. "What you're seeing is encampments that I haven't seen since the 80s," said Paul Boden, executive director of the Western Regional Advocacy Project, an umbrella group for homeless advocacy organizations in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, Calif., Portland, Ore. and Seattle. The relatively tony city of Santa Barbara has given over a parking lot to people who sleep in cars and vans. The city of Fresno, Calif., is trying to manage several proliferating tent cities, including an encampment where people have made shelters out of scrap wood. In Portland, Ore., and Seattle, homeless advocacy groups have paired with nonprofits or faith-based groups to manage tent cities as outdoor shelters. Other cities where tent cities have either appeared or expanded include include Chattanooga, Tenn., San Diego, and Columbus, Ohio. The Department of Housing and Urban Development recently reported a 12 percent drop in homelessness nationally in two years, from about 754,000 in January 2005 to 666,000 in January 2007. But the 2007 numbers omitted people who previously had been considered homeless -- such as those staying with relatives or friends or living in campgrounds or motel rooms for more than a week. In addition, the housing and economic crisis began soon after HUD's most recent data was compiled. "The data predates the housing crisis," said Brian Sullivan, a spokesman for HUD. "From the headlines, it might appear that the report is about yesterday. How is the housing situation affecting homelessness? That's a great question. We're still trying to get to that." In Seattle, which is experiencing a building boom and an influx of affluent professionals in neighborhoods the working class once owned, homeless encampments have been springing up — in remote places to avoid police sweeps. "What's happening in Seattle is what's happening everywhere else — on steroids," said Tim Harris, executive director of Real Change, an advocacy organization that publishes a weekly newspaper sold by homeless people. Homeless people and their advocates have organized three tent cities at City Hall in recent months to call attention to the homeless and protest the sweeps -- acts of militancy, said Harris, "that we really haven't seen around homeless activism since the early '90s."

In Reno, officials decided to let the tent city be because shelters were already filled. Officials don't know how many homeless people are in Reno. "But we do know that the soup kitchens are serving hundreds more meals a day and that we have more people who are homeless than we can remember," said Jodi Royal-Goodwin, the city's redevelopment agency director. Those in the tents have to register and are monitored weekly to see what progress they are making in finding jobs or real housing. They are provided times to take showers in the shelter, and told where to go for food and meals. Sylvia Flynn, 51, came from northern California but lost a job almost immediately and then her apartment. Since the cheapest motels here charge upward of $200 a week, Flynn ended up at the Reno women's shelter, which has only 20 beds and a two-week limit on stays. Out of a dozen people interviewed in the tent city, six had come to Reno from California or elsewhere over the last year, hoping for casino jobs. "I figured this would be a great place for a job," said Max Perez, a 19-year-old from Iowa. He couldn't find one and ended up taking showers at the men's shelter and sleeping in a pup tent barely big enough to cover his body. The casinos are actually starting to lay off employees. "Sometimes I think we need to put out an ad: 'No, we don't have any more jobs than you do,'" Royal-Goodwin said. The city will shut down the tent city as soon as early October because the tents sit on what will be a parking lot for a complex of shelters and services for homeless people. The complex will include a men's shelter, a women's shelter, a family shelter and a resource center. Reno officials aren't sure whether the construction will eliminate the need for the tent city. The demand, they say, keeps growing.

Economic Casualties Pile Into Tent Cities by: Emily Bazar

Pinellas County, Florida - Jim Marshall recalls everything about that beautiful fall day. The temperature was about 70 degrees on Nov. 19, the sky was "totally blue," and the laughter from a martini bar drifted into the St. Petersburg park where Marshall, 39, sat contemplating his first day of homelessness. "I was thinking, 'That was me at one point,' " he says of the revelers. "Now I'm thinking, 'Where am I going to sleep tonight? Where do I eat? Where do I shower?' " The unemployed Detroit autoworker moved to Florida last year hoping he'd have better luck finding a job. He didn't, and he spent three months sleeping on sidewalks before landing in a tent city in Pinellas County, north of St. Petersburg, on Feb. 26. Marshall is among a growing number of the economic homeless, a term for those newly displaced by layoffs, foreclosures or other financial troubles caused by the recession. They differ from the chronic homeless, the longtime street residents who often suffer from mental illness, drug abuse or alcoholism. For the economic homeless, the American ideal that education and hard work lead to a comfortable middle-class life has slipped out of reach. They're packing into motels, parking lots and tent cities, alternately distressed and hopeful, searching for work and praying their fortunes will change. "My parents always taught me to work hard in school, graduate high school, go to college, get a degree and you'll do fine. You'll do better than your parents' generation," Marshall says. "I did all those things. Ö For a while, I did have that good life, but nowadays that's not the reality." Tent cities and shelters from California to Massachusetts report growing demand from the newly homeless. The National Alliance to End Homelessness predicted in January that the recession would force 1.5 million more people into homelessness over the next two years. Already, "tens of thousands" have lost their homes, Alliance President Nan Roman says. The $1.5 billion in new federal stimulus funds for homelessness prevention will help people pay rent, utility bills, moving costs or security deposits, she says, but it won't be enough. "We're hearing from shelter providers that the shelters are overflowing, filled to capacity," says Ellen Bassuk, president of the National Center on Family Homelessness. "The number of families on the streets has dramatically increased." "A Change in the Population" Pinellas Hope, the tent city run by Catholic Charities here since December 2007, has been largely for the chronically homeless, some of whom suffer from mental illness or struggle with drugs or alcohol. About 20% of its 240 residents became homeless recently because of the economic downturn, says Frank Murphy, president of Catholic Charities, Diocese of St. Petersburg. "We're seeing a change in the population. Ö We're seeing a lot more that are just plain losing their jobs and their homes," says Sheila Lopez, chief operating officer of the charity. "A lot are either job-ready or working but have lost their home because they were laid off, or their apartment, and now can't go to work because they're not shaven, they're not clean, they're living in a car, or they're living on the street." The charity plans to expand the tent city and build an encampment in a neighboring county, an idea that has drawn objections from nearby homeowners and businesses. Communities elsewhere are facing similar pressures: In Massachusetts, a record number of homeless families need emergency shelter, says Robyn Frost, executive director of the Massachusetts Coalition for the Homeless. In mid-April, there were 2,763 families in shelters, including 655 in motels because the shelters were full, an increase of 36% since July, she says. "We have a high number of foreclosure properties, and many of them are multifamily apartments," Frost says. "We were seeing a great number of families being displaced." Reno officials shut down a tent city in October after making more shelter space available, but new encampments are popping up along the Truckee River and elsewhere, says Kelly Marschall of the Reno Area Alliance for the Homeless. The homeless include "a startling number of first-time homeless," she says. "We asked them what industries they were involved in. The majority were talking about construction, the housing industry, real estate. There was a direct correlation to the housing market crash." In Santa Barbara, Calif., 84 men and women sleep in their cars, trucks or recreational vehicles in 17 parking lots around the city, says Jason Johnson with the New Beginnings Counseling Center, which runs the RV Safe Parking Program. The city, which allows the use of three municipal lots at night, supports the program, says city parking superintendent Victor Garza. Last May, there were 58 participants and no waiting list. Now 40 people are waiting. "People's last refuge has become their vehicle," Johnson says. Objections by Residents Pinellas Hope in Florida looks like a cookie-cutter subdivision, except that the orderly rows are of tents, not houses. Besides 250 tents, all of similar size, shape and color, there are 15 wooden sheds, 6 feet by 8 feet, that Catholic Charities built as shelters. The charity plans to reduce the number of tents to 150 and erect 100 sheds, which are more durable, and build as many as 80 permanent studio apartments on the property, Murphy says. His group also wants to open a campground for 240 homeless people in neighboring Hillsborough County, he says, primarily using wooden sheds. Unlike Pinellas Hope, which doesn't border residential neighborhoods, the Hillsborough County parcel is across the street from a tidy 325-home subdivision called East Lake Park. There, opponents of the tent city have a website: www.stoptentcity.com. Hal and Cindy Hart are raising three grandchildren in their home on the lake. The kids, 4 to 13, fish for bass, ride their bikes to friends' houses and attend neighborhood parties. The Harts fear that large numbers of homeless people, some with addictions and criminal backgrounds, would loiter in the neighborhood. "We will not be able to let our grandchildren ride their bikes outside without constant supervision," says Hal Hart, 52, a paralegal. The Harts agree that the homeless population needs services, but they think the emphasis should be on programs that will help families, not single adults. Murphy says the diocese wants to address the neighbors' concerns and has lowered the number of proposed occupants from 500. "A temporary situation" Pinellas Hope, which has a waiting list of about 150 people, is attracting a growing stream of homeless men, women and couples. Families with children are sent to area shelters. New arrivals must agree to rules, such as not using drugs or alcohol, and perform chores, Lopez says. They get mats, sleeping bags, toiletries, flip-flops for showers and lockable boxes in their tents to store valuables. Within one week, they must make a plan describing how they will work their way out of homelessness. Residents are expected to move on within five months, but some stay longer. Campers have access to trailers with bathrooms, showers, computers, washers and dryers and a room of donated clothes. They get a free bus pass the first month and advice on writing resumes. By day, some leave camp to look for work or ride the bus to pass the time. Others stay, watching TV in large communal tents, doing laundry or playing Monopoly. At night, an off-duty police officer patrols the camp, which is governed by curfews: 10:30 p.m. on weeknights and midnight Fridays and Saturdays. The camp bustles at dinnertime, when everyone gathers for a hot meal provided by churches and other organizations. A year ago, there were 5,500 homeless people in Pinellas County, says St. Petersburg police officer Richard Linkiewicz, a homeless-outreach officer. This year, there are 7,500, including 1,300 children in homeless families, he says. Many of the newly homeless worked in construction, a booming industry in Florida before the economic bust, he says. David Grondin, 48, moved in on Feb. 7 and stayed for two months. A union carpenter, he graduated from the University of South Florida in 1999 with a bachelor's degree in fine arts. He struggled as carpentry work and odd jobs disappeared. When his 1992 Saturn died in August, he could no longer get to jobs far from public transportation routes. Frustrated by his inability to find a job in Florida, last month Grondin took a bus to Portland, Maine, where he's staying with friends and looking for carpentry work. "I was definitely middle class," he says. "I had a car. I got a paycheck every week." Kevin Shutt, 53, moved into Pinellas Hope in March after he was laid off from his job waiting tables because diners "stopped coming through the doors," he says. Shutt has decorated his tent with house plants, including a ficus tree his mother gave him nearly 30 years ago, and pinned Tampa Bay Rays and Buccaneers jerseys to the inside walls. He tearfully recounts how he got kicked out of his apartment by a roommate when he couldn't come up with the rent. A former homeowner who made Caesar salads tableside at restaurants, now he can't get a job at Taco Bell, he says. "This is the first time in my life I ever dreamed about living in a tent," he says. An optimist by nature, Shutt vows that his stay will be short. He has filled out more than 175 job applications and occasionally works for a friend doing canvas work on boats. "This is a temporary situation," he says. A Diminished Outlook Marshall, the former autoworker, has an associate's degree in electronic engineering and is less encouraged. He remembers a comfortable life in Michigan, where he worked in automotive testing, owned a brick ranch-style home, made up to $50,000 a year and played in softball leagues. Companies he worked for started losing contracts a few years ago, and eventually the work dried up, he says. He sold his house and moved into an apartment, but by 2007 he couldn't pay the rent. He came to Florida in August, thinking the job market was better. But he couldn't pay the rent here, either. At Pinellas Hope, Marshall searches online job sites or takes the bus to apply for work at McDonald's, factories and Wal-Mart. He gets $45 a week selling his blood plasma. "I have my rÈsumÈ online. I go door to door. I make phone calls," he says. "I have not received one phone call, one e-mail. I thought with my experience and my degree, it wouldn't be this difficult." Marshall feels ill at ease in the camp and has trouble sleeping, and not just because of the armadillos that burrow under his tent. "I'm scared," he says. "If I can't find a job, where do I go next?" At this point, he has lowered his expectations. "I don't expect ever to make $50,000 a year working in the auto industry, but just enough to survive, have my own place, buy my own food, my own clothes," he says. "What every American would expect."

Comments:

|

Hunkin walked past a pit bull puppy and peered over a makeshift shelter of tents and tarp hidden by koa haole and elephant grass, then pointed toward the high school's athletic complex barely a football field away.

Hunkin walked past a pit bull puppy and peered over a makeshift shelter of tents and tarp hidden by koa haole and elephant grass, then pointed toward the high school's athletic complex barely a football field away. "It's clear that poverty and homelessness have increased," said Michael Stoops, acting executive director of the coalition. "The economy is in chaos, we're in an unofficial recession and Americans are worried, from the homeless to the middle class, about their future."

"It's clear that poverty and homelessness have increased," said Michael Stoops, acting executive director of the coalition. "The economy is in chaos, we're in an unofficial recession and Americans are worried, from the homeless to the middle class, about their future."