Entoptic artifacts as universal trance phenomena

By Floco Tausin [above: Alfred Dam aus der Schweiz Beschreibung: Aus der Serie "Inbetween Heaven and Earth", 1999] In the mid-1990s the author met a man named Nestor living in the solitude of the hilly Emmental region of Switzerland. Nestor has a unique and provocative claim: that he focuses for years on a constellation of huge shining spheres and strings which have been formed in his field of vision. He interprets this phenomenon as a subtle structure formed by our consciousness which in turn creates our material world. Nestor, who calls himself a seer, ascribes this subjective visual perception to his long lasting efforts to develop his consciousness. He explains his vision as an extended perception of a phenomenon for which, in ophthalmology, the collective term "floaters" is applied.

As physical and neurological symptoms, they belong to the physicians' area of study; as subjective light phenomena they are likely to gain spiritual meanings for people like Nestor. While the Western medical study of entoptics has a tradition of a couple of hundred years, the interpretation of entoptic phenomena like floaters as spiritually significant perception in connection with altered states of consciousness possibly originated in the early days of human art. Stone age rock art as entoptic phenomena -- a study In the 19th century, European and American opticians, physiologists and philosophers developed a broad interest in entoptic phenomena. To generate and study entoptics, they conducted experiments by stimulating brain and retina, electrically at first, later also with mind-altering substances. Especially in the 1960s and 70s, a number of experiments on subjects were conducted using agents such as THC the active ingredient in marijuana), mescaline, psilocybin and LSD. A worldwide ban on these substances interrupted the drug based research on entoptic phenomena.

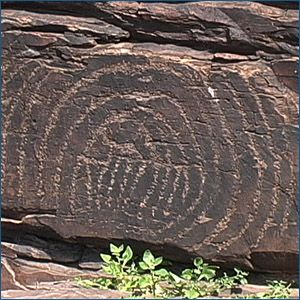

Ever since the discovery of the European Paleolithic caves, archaeologists have been wondering about the importance and meaning of such geometric representations. Attempts to explain them in terms of totemism or magical rituals were hardly convincing to the research community. Lewis-Williams and Dowson brought forward the original thesis that Paleolithic art is inspired by subjective visual phenomena, seen and depicted by shamans or spiritual men and women during altered states of consciousness. As subjective visual phenomena they understand, on the one hand, visual hallucinations, and on the other hand, entoptic phenomena which are colored or bright moving geometric shapes and patterns. Lewis-Williams and Dowson, as well as the researchers following their train of thoughts, focused on the entoptic phenomena. For while the visual hallucinations are shaped in an individual by cultural factors, entoptic phenomena are said to be culturally independent, generated by states of the visual nervous system only. Moreover, two kinds of entoptics are distinguished: the phosphenes -- light phenomena whose origin can be traced back to physical stimulation of the eyeball, and the so-called "form constants" -- geometric shapes that occur in altered states of consciousness.

The researchers developed a neuropsychological model to classify the geometric forms in six types -- grid, lines, dots, zigzag lines, catenary curves, and filigrees -- and to describe the progressive stages of the visual trance experience, starting with abstract entoptic forms that gradually transform into iconic images corresponding with the everyday or mythic reality of the shaman.

They tested their model, analyzing the art of two current shamanic societies: the South African San and the US American Great Basin Shoshone community Coso. Finally, the authors applied their model to carved and painted stone age rock art, and affirmed their hypothesis that this art, too, was created in the context of shamanism and altered states of consciousness. Critique of the model and further studies The study by Lewis-Williams and Dowson inspired researchers beyond archaeology to further investigate the relationships of (prehistoric) art, shamanism and entoptic phenomena -- and found them in other regions and times as well. Critics, on the other hand, refuted the relationship between the rock art geometric figures, entoptic phenomena and shamanism. Abstract art, they argued, is not an evidence for entoptic phenomena or shamanic practices, as abstract forms appear also in non-shamanistic communities or even in doodles of young children. Today, the topic is somewhat abated. The thesis of Lewis-Williams and Dowson could not be wholly confirmed or refuted. To this author, the thesis seems plausible if we draw attention to the present: the anthropologist Erika Bourguignon notes that of 488 societies, 437 know institutionalized forms of change of consciousness states. It is exactly these altered states of consciousness that form the intersection between the perception of entoptic phenomena and intense religious experiences. Thus, the probability is very high that most societies that lived and live on this planet not only were aware of entoptic phenomena but also gave them cultural or religious significance. The 1991 master thesis by American anthropologist Linda Thurston supports this claim. Thurston provides a number of examples of anthropologists examining the hallucinogenic art of indigenous people and explaining it in terms of changes in the neurophysiological visual system. Even if most of these anthropologists are not explicitly referring to entoptic phenomena, it's not difficult to see similarities in the abstract patterns of the Indian art in Peru, including the famous Nazca lines, the art of the Tukano societies of the Colombian Amazon region, the yarn paintings of the Huichol Indians in Mexico, the so-called "grecas" of North American Indian art etc. Thurston herself points to the entoptic patterns in the art tradition of Australian Aboriginal Dreaming. All these societies are or were working with altered states of consciousness which were brought about in religious rituals through various techniques and means.

Entoptic imagery in (religious) art most probably spread beyond indigenous cultures. Some of the symbols of more elaborated and institutionalized religious traditions might originally trace back to entoptic patterns seen in altered states of consciousness. For example: abstract representations of the Egyptian sun god (Re/Ra) and the Mesopotamian sun disk and winged sun, the Hindu and Buddhist yantras, mandalas, and abstract representations of chakras, the Indian sun wheel (swastika), the arrangement of the ten Kabbalistic Sefirot, as well as certain representations of the Christian cross. In Western modern societies, some artists are working with subjective visual and entoptic phenomena, though not necessarily in a religious or spiritual context. Conclusion Entoptic phenomena have been significant for many societies throughout history. They have been observed, recorded and interpreted by spiritual women and men over and over. This way, entoptics entered into particular cultures, as a source of inspiration for artists, philosophers and religious thinkers and believers alike. However, there have always been societies in which entoptic phenomena had no wider cultural significance, as it is the case with industrialized Western societies. Since the early modern triumph of Western materialism, the physical world is the exclusive objective, everyday perception and concentration. Anything that goes beyond that, like dreams, hallucinations, visions and entoptic phenomena, has no obvious benefit to society and economy. Common sense, therefore, deems perceptions like that as "disturbance" or worse, to be treated medically and psychologically. This author finds this problematic in an age in which the negative effects of a one-sided focusing on materialistic ideals are evident. Modern society has caused global, social, and individual problems, but cannot deal with these by its own means of technology and rationality -- not as long as the same ideals govern the minds of the people. Many people have recognized the problem and orient themselves to new intellectual and spiritual values. The visual path conveyed by consciousness researchers of past and present societies is a possible approach to literally focus on the "spiritual" rather than the "material". The mobile dots and strands called "eye floaters" offer themselves as a particularly suitable meditation object. Unlike other entoptic phenomena, floaters are visible in our everyday state of consciousness, and we can move them in our visual field anytime, play with them, focus on them and try to hold them in suspension.

|

In ophthalmology, eye floaters are generally regarded as harmless vitreous opacities [right]. They are "entoptic phenomena", viz. optical phenomena which are caused by certain conditions of the human visual system. Entoptic phenomena, whose appearance can be manipulated by selectively induced changes of consciousness states, are objects of interest for both science -- and spiritually -- oriented researchers.

In ophthalmology, eye floaters are generally regarded as harmless vitreous opacities [right]. They are "entoptic phenomena", viz. optical phenomena which are caused by certain conditions of the human visual system. Entoptic phenomena, whose appearance can be manipulated by selectively induced changes of consciousness states, are objects of interest for both science -- and spiritually -- oriented researchers.  In 1988, two South African archaeologists referred to this heritage of the 1960s and 70s when they presented an alternative interpretation of stone age rock art of a certain kind. In a sensational publication,

In 1988, two South African archaeologists referred to this heritage of the 1960s and 70s when they presented an alternative interpretation of stone age rock art of a certain kind. In a sensational publication,  Lewis-Williams and Dowson emphasize that our nervous system does not differ from that of prehistoric man. This means that we can perceive the same entoptic phenomena as people did 40,000 years ago. This circumstance allows the researchers to carry out comparisons between past and present art in different cultural contexts in order to support their argument.

Lewis-Williams and Dowson emphasize that our nervous system does not differ from that of prehistoric man. This means that we can perceive the same entoptic phenomena as people did 40,000 years ago. This circumstance allows the researchers to carry out comparisons between past and present art in different cultural contexts in order to support their argument.